Nel 1578, John Florio pubblicò la sua prima opera, First Fruits, che contiene quattro poesie dedicatorie scritte dall’intera compagnia dei Leicester’s Men: Richard Tarlton, Robert Wilson, Thomas Clarke e John Bentley. Essi ringraziano John Florio per aver contribuito a portare i narratori italiani nel teatro inglese. Le dediche dimostrano che Florio era in contatto con la compagnia teatrale molto prima dell’arrivo di William Shakespeare in città; i componimenti indicano che Florio era il tutore e maestro della compagnia teatrale e che collaborò con loro nella stesura delle opere. Giulia Harding e Chris Stamatakis 1 hanno sostenuto che John Florio facesse parte di una “rete teatrale” insieme alla compagnia dei Leicester’s Men. Anche Stephen Greenblatt 2 afferma che vi siano prove che “già nei primi anni 1590 egli [Florio] fosse un uomo altamente familiare con il teatro.”

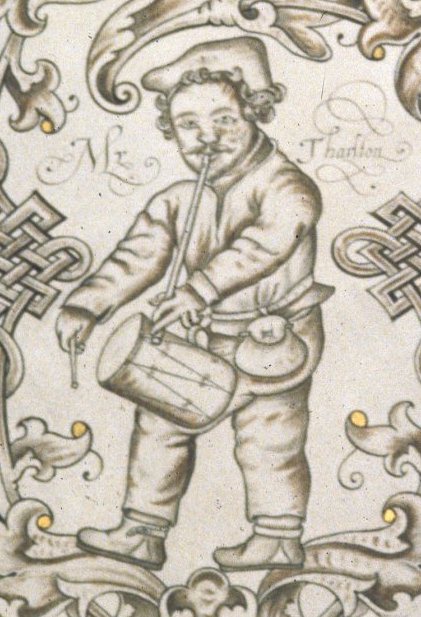

Richard Tarlton (morto nel settembre 1588) fu un attore inglese dell’epoca elisabettiana. È considerato il clown più celebre del suo tempo, noto per i suoi versi comici estemporanei in stile doggerel, che presero il nome di “Tarltons”. Contribuì a trasformare il teatro elisabettiano in una forma di intrattenimento di massa, aprendo la strada al palcoscenico shakespeariano. Dopo la sua morte, numerosi motti di spirito e scherzi gli furono attribuiti e pubblicati nella raccolta Tarlton’s Jests. Tarlton era anche un eccellente ballerino, musicista e schermidore. Inoltre, fu uno scrittore prolifico, autore di numerosi jigs, opuscoli e almeno un’opera teatrale completa. Scopri di più su Richard Tarlton.

Richard Tartlon in prayse of Florio

“If we at home, by Florios paynes may win,

Se noi, grazie agli sforzi di Florio, possiamo qui, a casa nostra,

to know the things that travailes great would aske:

conoscere ciò che richiederebbe grandi viaggi;

By openyng that, which heretofore hath bin a daungerous journey,

aprendo ciò che prima era un viaggio pericoloso

and a feareful taske. Why then ech Reader that his Booke doe see,

e un compito spaventoso. Allora, ogni lettore che vedrà il suo libro,

Give Florio thankes, that tooke such paines for thee.”

ringrazi Florio, che si è affaticato così tanto per te.

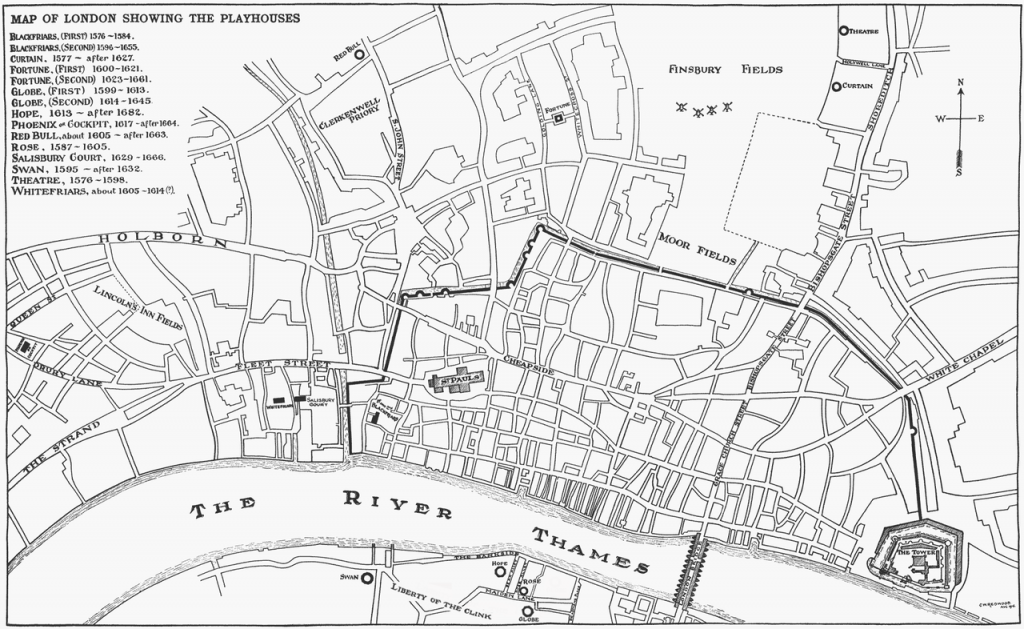

The Theatre, 1576-1598

Il Theatre è indicato nell’angolo in alto a destra di questa mappa stradale di Londra. Fu nel periodo in cui Florio stava scrivendo First Fruites che il primo teatro pubblico in Inghilterra venne inaugurato a Londra da Richard Burbage nel 1576. Il Theatre rimase aperto dal 1576 al 1598, ospitando rappresentazioni teatrali fino alla sua chiusura. Situato a Shoreditch, il teatro fu costruito da James Burbage, che lo chiamò “Theatre” per evocare l’idea di un teatro romano o theatrum. Divenne estremamente popolare tra i primi spettatori londinesi. Scopri di più sul Theatre.

Robert Wilson in prayse of Florio

The pleasant fruites that FLORIO frankly yeeldes,

I frutti piacevoli che FLORIO generosamente offre,

unseene tyl now, saue in Italian soyle:

mai visti prima, se non nel suolo italiano,

May quickly florish in our English fieldes,

possono presto fiorire nei nostri campi inglesi,

if in this woorke we take but easie toyle.

se in quest’opera ci dedichiamo con un minimo di fatica.

He sets, he sowes, he plants, he proynes with paine,

Egli pianta, semina, coltiva e pota con cura,

the seedes, and Cienes farre fet from forraine landes:

semi e tralci provenienti da terre lontane;

And geues vs (idle) both the stocke and graine,

e ci dona (noi oziosi) sia la radice che il grano,

even his firste fruites the ioy of labouring handes.

proprio i suoi primi frutti, la gioia di mani operose.

We geue hym nought, if we can not deuise to giue him thankes,

Non gli diamo nulla, se non sappiamo concepire

that may hym wel suffice.

di offrirgli ringraziamenti che possano bastargli.

Swan Theatre

Nel Palladis Tamia (1598), Francis Meres menziona Wilson insieme a Tarlton e collega specificamente Wilson allo Swan Theatre, costruito intorno al 1595.

John Bentley in commendation of his friend I.F.

You English Gentlemen that craue,

Voi, gentiluomini inglesi, che desiderate

the fine Italian tongue to knowe:

conoscere la raffinata lingua italiana,

And you Italians that would haue,

e voi italiani che volete avere

a Rule the English speach to showe:

una guida per la lingua inglese,

Geue FLORIO thankes, whose first fruites teach,

ringraziate FLORIO, i cui primi frutti insegnano

Howe you the grounde of both may reach.

come raggiungere le basi di entrambe.

John Bentley, amico di John Florio, fu uno degli attori principali dei Leicester’s Men e della compagnia della regina (Queen’s Men), fondata nel 1583, la più importante organizzazione drammatica dell’epoca. Evidentemente, godette di una grande fama contemporanea: ventidue anni dopo la sua morte, era ancora conosciuto come “l’inimitabile Bentley.” Nell’immagine: The Famous Victories of Henry V (c. 1583), una delle opere di maggior successo messe in scena dalla compagnia della regina. Il dramma presenta venti personaggi parlanti nei primi 500 versi; le opere successive, incluse le storie scritte da Shakespeare, sono costruite su una scala simile.

Thomas Clarke in commendation of Florio

No labour wantes deserued meede,

Non vi è fatica che non meriti ricompensa,

no taken toyle is voyde of gaine:

nessun lavoro preso che non sia privo di guadagno.

No grounde so barren, but the seede,

Nessun terreno così sterile, ma il seme,

and somewhat more wyl yeelde for paine,

e un po’ di più darà per la fatica.

For paine? why then should FLORIO feare,

Per fatica? E allora, perché dovrebbe temere FLORIO,

To reape the gaine, he merites heare.

di raccogliere il guadagno che merita qui?

Which gaine, is onely good report,

Questo guadagno, è solo una buona reputazione,

and honour due for taken toyle.

e l’onore dovuto alla fatica sopportata.

Which graunt hym wyl the wiser say so,

Che gli venga concesso, dicono i più saggi,

for whom he tylles this fertile soyle.

per chi lavora questa fertile terra.

And settes the slips in English lande,

E pianta i tralci in terra inglese,

of Tuscane tongue, to spring and stande.

della lingua toscana, per farli germogliare e stare.

As for the rest, if they requite,

Quanto al resto, se non ricambiano,

his labour yl, what may he say?

il suo lavoro, cosa potrà mai dire?

I have this done for their delight,

Ho fatto questo per il loro piacere,

and they for paine disdaine me pay.

e loro, in cambio, disdegnano di pagarmi per la fatica.

Ma non importa, sith this so,

Ma non importa, poiché così è,

Ile please the best, the rest shal go:

piacere ai migliori, il resto se ne vada:

Bent to content.

piegato per contentare

The same in French.

La stessa in francese

Qui voudra voir & auoir

Chi vorrà vedere e avere

La Science, e le scaouir

la scienza e la conoscenza

De la Langue Italienne

della lingua italiana,

FLORIO l’ha escrit

FLORIO l’ha scritta

Pour nostre gran deduit

per nostro grande diletto.

A infi come il auienne.

Così come avviene.

Donques ensa Louange

Allora, in lode

Faisons nous vers estrange

facciamoci versi strani

Et en Langue estrange ausi.

e in lingua straniera anch’essa.

Pour son gran Labeur pris

Per la sua grande fatica presa,

Il en aura le pris

egli avrà il premio,

Le bien de son enuy.

il bene della sua fatica.

Bibiografia

De Francisci, Enza, and Chris Stamatakis, eds. Shakespeare, Italy, and Transnational Exchange: Early Modern to Present. 2017.

Greenblatt, Stephen. Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. Pimlico, 2005